I am watching Lawrence of Arabia on YouTube on an ultra-high-definition television in my living room. As I watch the protagonist crash and die on a motorbike, I realise true cinephiles would call out this crime. The crime of watching a 70 mm epic on a digital platform and on YouTube nonetheless, home to an ocean of cat and dog videos. I do faintly remember having seen the movie in the company of my father years ago, probably on VHS when I was too young to comprehend the scale and brilliance of David Lean’s epic.

During my re-watch of the British epic biographical drama, I realise the masterpiece it is. Imagine if it were not to have a theatrical release and you had to watch it on streaming television, would it have the same effect? A hidden gem pushed by algo driven suggestions. Would it be the same on a 6.5-inch mobile screen? What if algos did not recommend Lawrence of Arabia, would cinema be the same? Would we have a Steven Spielberg?

The imagery strikes me with a hard blow, and it dawns upon me much like the rising sun on screen; the content, sorry cinema, was originally made for 70mm theatre. Each frame stands out with its enchanting desert landscapes and dark hills. You can almost feel the isolation and blazing heat of the scene playing out on the screen. Well almost, considering it’s on YouTube and not on a 70mm screen.

It’s hard to conceive David Lean’s storytelling as instant content while an on-screen button prompts me to skip an ad for Axe deodorant. My thoughts wander- does the algo think I have BO? Such is the nature of online content and yet here I am watching this 70 mm epic on the heroic life of T. E. Lawrence (Peter O’Toole).

What makes great cinema? That’s a question cinephiles the world over have obsessed over, over and over again even while leaving Martin Scorsese in a state of distress.

Would it be the same if the stunning imagery captured by Freddie Young with Super Panavision lenses for which he won the Best Cinematography – Colour at the ’63 Academy Awards had been shot in cinematic mode on an Iphone? Only Steve Jobs would have the audacity to convince David Lean to do that.

Anne V. Coates won an Oscar for best film editing and had 33 miles of film to review and decide which parts to keep and which parts to cut. Not a TikTok short or an Instagram reel.

I move on as the desert and the characters draw me into the story. The desert landscapes appear as if they were plucked from a masterpiece by a great artist in sharp contrast to frames from contemporary superhero movies rich in synthetic graphics and computer-generated illustrations which one might, just might also find in a children’s coloring book.

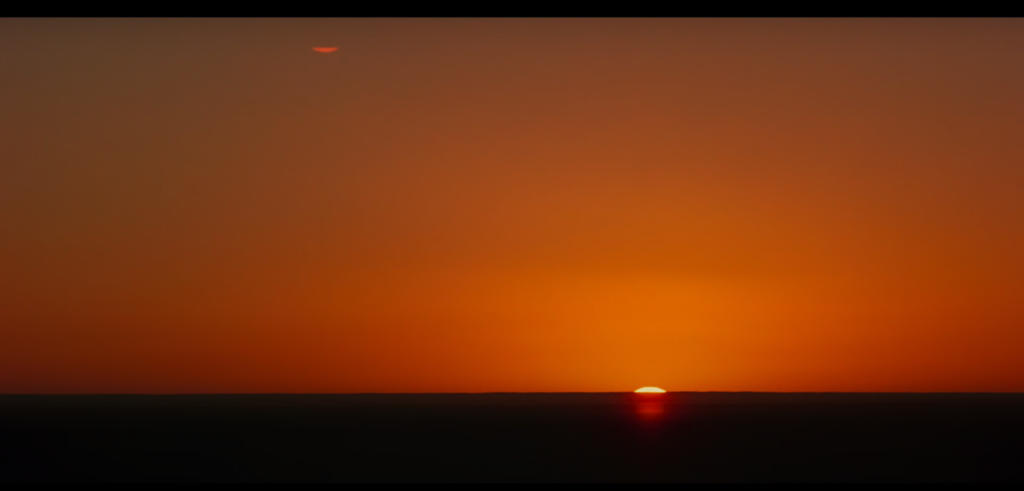

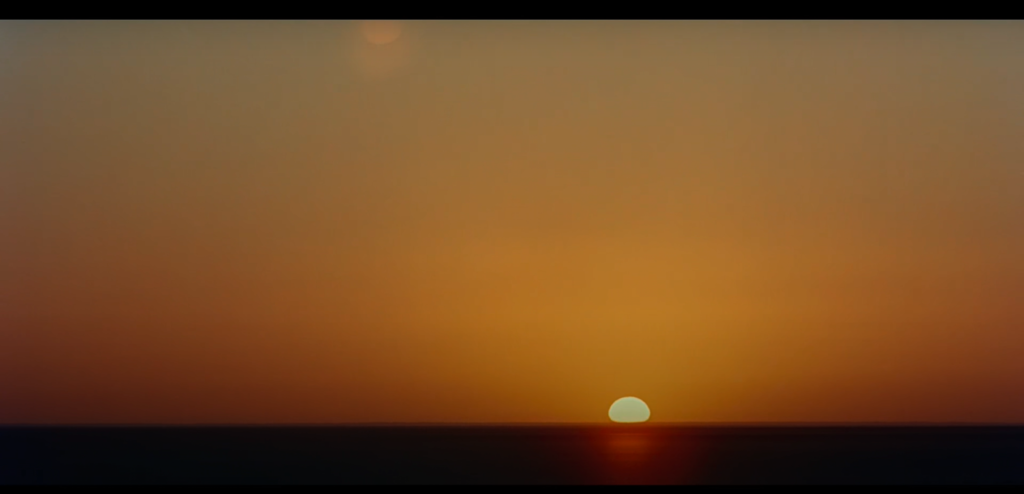

The close-up of Lawrence blowing out the lit matchstick cutting away to the long shot of the rising sun gives us an inkling of what David Lean has in store for us with the warm colours of the desert landscape and leading lines of the horizon creating a sense of depth, direction, and movement within the frame. The movement is always, almost always from left to right.

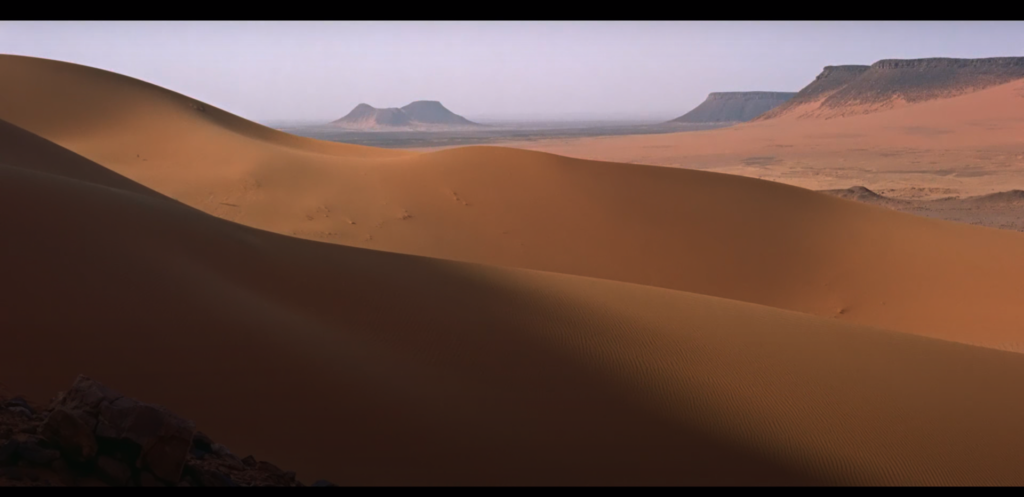

The shots where we have desert dunes which always seem to be unspoiled without even the lightest of tread marks beyond what is made by the desert wind and the footprints of the camels. And of sand displaced by the temperament of nature which encases the landscape.

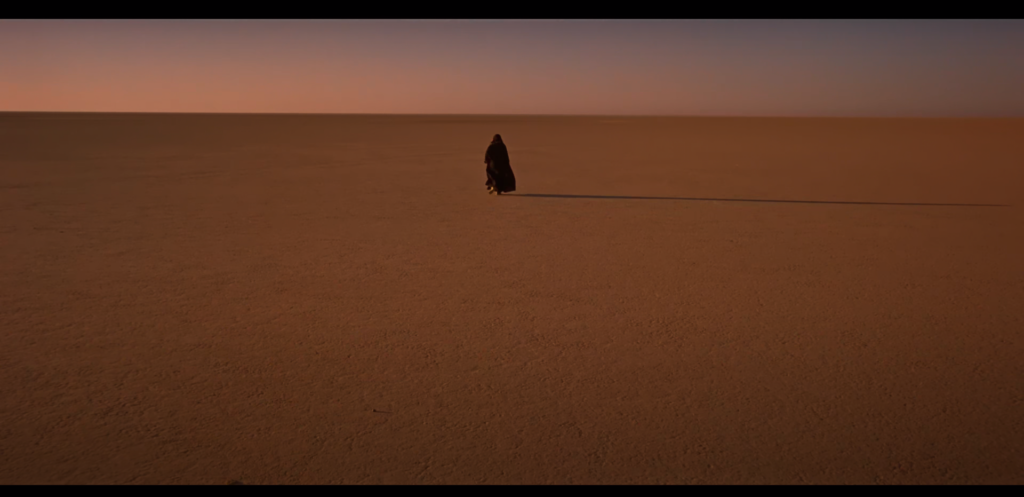

The opening scenes of the desert look warm and welcoming to the travellers and the vastness of the desert magnified by its void emptiness and silence which embraces it is felt. “The desert is clean,” says Lawrence.

The characters are seen moving from left to right indicating a journey or passage.

In the first half, the long shots of Lawrence with Tafas, his Bedouin guide, have stunning views of the desert landscape and the dark hills. Shot on location in the deserts of Jordan and Morocco the film with its 70 mm canvas does complete justice to the setting.

Lawrence and Tafas ride away into the distance between the hills creating a soulful onscreen rendering, a frame that could literally be hung on a wall with its perfect composition crafted out of nothing but sand and rocks.

The discovery of the only water-well for miles on their journey to find Prince Faisal (Alec Guinness) and the entry of Sherif Ali (Omar Sharif) through the mirage is flawless in every aspect. This scene shot with a 500 mm Panavision lens stands apart from contemporary scenes in the history of filmmaking. Sherif Ali emerges from the distant horizon as a speck, slowly becoming larger and larger until he looms upon Lawrence and Tafas as a threat.

The quietness of the setting with the desolate background quickly followed by the gunshot aimed at the head of Tafas by Sherif Ali leads to Lawrence’s first encounter with Sherif Ali. The bitterness of the desert slowly reveals itself.

Further on David Lean introduces Prince Faisal (Alec Guinness) riding horseback, scimitar in hand chasing Ottoman war planes firing at the Arab rebels. I add an interesting bit of trivia here- David Lean dropped a project on Gandhi which he had planned to make with Alec Guinness in the lead as the Mahatma.

Lean leads us on to T. E. Lawrence’s (Peter O’Toole) love for the desert as he walks into the desert night to contemplate a miracle, a miracle Prince Faisal (Alec Guinness) longs for. The scene beautifully lit and shot with filters at day as can be seen from the shadows conveys a message of longing for solitude as Lawrence embraces it.

T. E. Lawrence (Peter O’Toole) sits in the desert night to contemplate a miracle as his stalkers watch over him. Again, beautiful play of light and shadows.

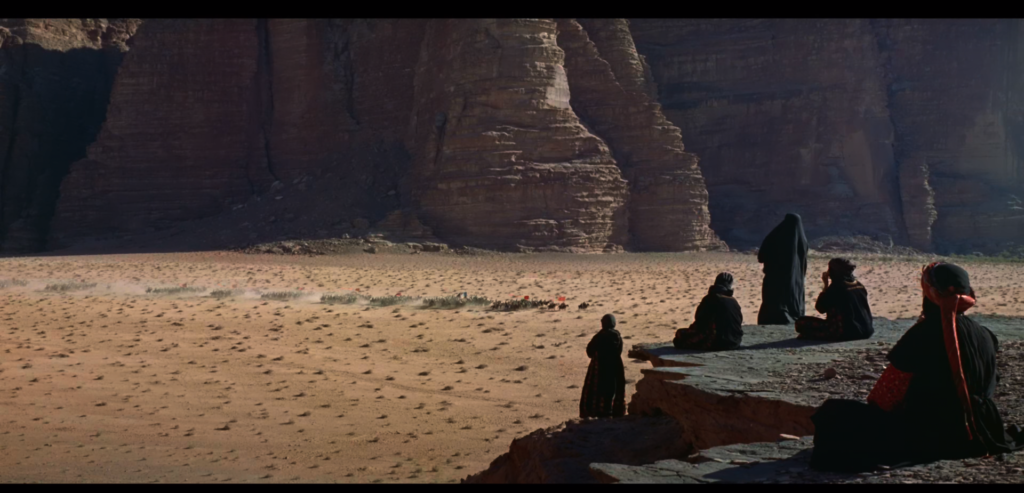

Prince Faisal accepts Lawrence’s idea and grants him 50 of his men to cross the desert to attack Aqaba. The scene has many layers with the camel cavalry in the foreground and desert plains and hills stretching into the back.

The vastness of the desolate land with its dry and harsh elements making the camel cavalry with its riders’ mere flecks in the desert landscape.

Lean has painted many scenes with the horizon indicating the culmination of where they need to be. The varied textures of the landscape with several layers of grey and blue have been spectacularly captured on camera making us feel the abrasive and bumpy road ahead impelling the viewer to take part in the journey.

The close-up of the rocks gives a notion of trepidation and a twinge of anguish on the dreadful passage ahead.

Gasim (I. S. Johar) falls off his camel and is separated from the rest of the Arab party led by Lawrence and Sherif Ali.

The sun rises at the horizon as Gasim (I. S. Johar) walks alone unravelling the danger of the blazing sun that awaits him as day breaks.

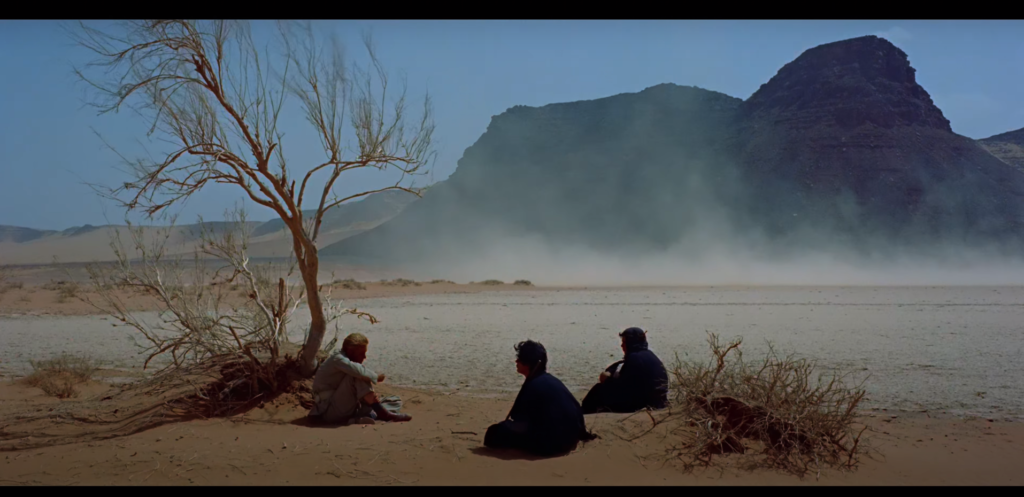

In a beautiful set of scenes Lean tells a story within a story. Gasim (I.S. Johar), a compatriot in the cavalry, falls off his camel from fatigue and is separated from the convoy only to be rescued later in a daring mission by Lawrence riding on nothing but hope and a camel. The isolation of Gasim is to be seen as he walks alone tracing his steps back to the convoy.

This is one of the rare scenes where you have the camel and its rider facing to the left in contrast to all the other scenes where you have them moving from left to right.

The desolate landscape as Gasim (I. S. Johar) walks alone.

This scene captures Gasim’s reaction from exhaustion and fatigue in the blazing desert sun. Shot from a high angle, the camera captures the dry floor. The next shot incredulously cuts to camels quaffing on water from a pond.

Lawrence’s (Peter O’Toole) flunky waits for him to return from the rescue. Another beautiful scene with the rich saturated blue sky in the background and the camel with its rider in sharp focus.

Lawrence’s flunky is thrilled upon seeing him return and the joy can be felt as they reunite.

Lawrence looks at his reflection in the dagger, the only mirror at hand to gaze at himself in the new garb gifted by the Bedouins- – a shemagh and thawb as they accept him as one of their own.

The magnificent vastness of the desert hosts the tribes led by Sherif Ali and Auda Abu Tayi.

The attack on Aqaba with Auda Abu Tayi (Anthony Quinn) leading the charge.

A camel rider at the sea. How often does one see that? Lawrence relishes the unexpected victory at Aqaba and takes a moment to reflect gazing at the sea.

Lawrence now takes up another perilous journey across the desert to Cairo to inform his superiors of the victory at Aqaba.

The journey towards Cairo after losing a companion to the desert. Lawrence is dejected and shocked at the desert taking the life of a friend. Covered with dust and dismay it is no longer clean.

A flawless frame of Lawrence standing victorious after his band of Bedouins reinforced with British supplies of an armed car and guns raid a Turkish train.

Lawrence poses after a victorious raid on a Turkish train between Medina and Damascus. Lawrence in his white robes with his arm pointed upwards is full of symbolism.

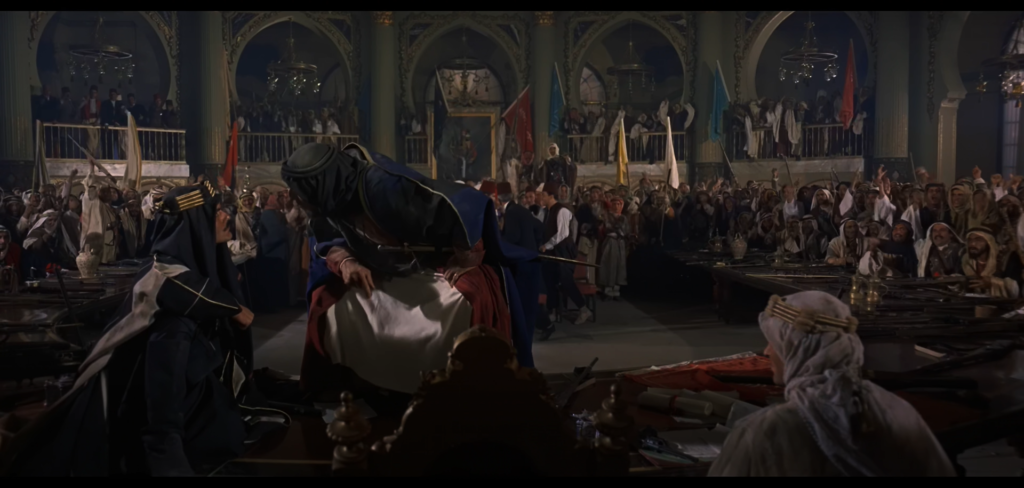

The peregrination of Lawrence reaches a culmination and ends with bitter-sweet victory. Lawrence ends with triumph at Aqaba but fails at bringing together the Arab tribes at Damascus.

The scenes at the Arab council meeting are filled with chaos and disorder and cacophony of voices trying to outmatch the other. The utter confusion and havoc at the gathering to the dismay of Lawrence is felt by the viewer as each tribe speaks for themselves and not as a whole.

Lawrence is deftly shunted out of Arabia by his commanding officer and Prince Faisal sees no more value in him. The last scene captures Lawrence riding a jeep on a desert track out of Arabia where he sees a soldier on a motorbike crossing his path reminding us we have reached the end of a journey just as Lawrence.

As the credits roll, I can’t help but reflect about watching the 70mm movie in the age of Netflix. There’s something undeniably special about stepping into a cinema which cannot be experienced at home on television.

Netflix and other streaming platforms have revolutionised the way we consume media, allowing us to watch content on our own terms, in the comfort of our homes. But they can never fully replicate the grandeur and spectacle of a 70mm movie. What is undeniable is that we have access to any movie, and I must thank the kind soul who uploaded an excellent print to preserve and archive movies of a bygone era for the future generations who may have the opportunity to experience it only on digital platforms.

Leave a Reply