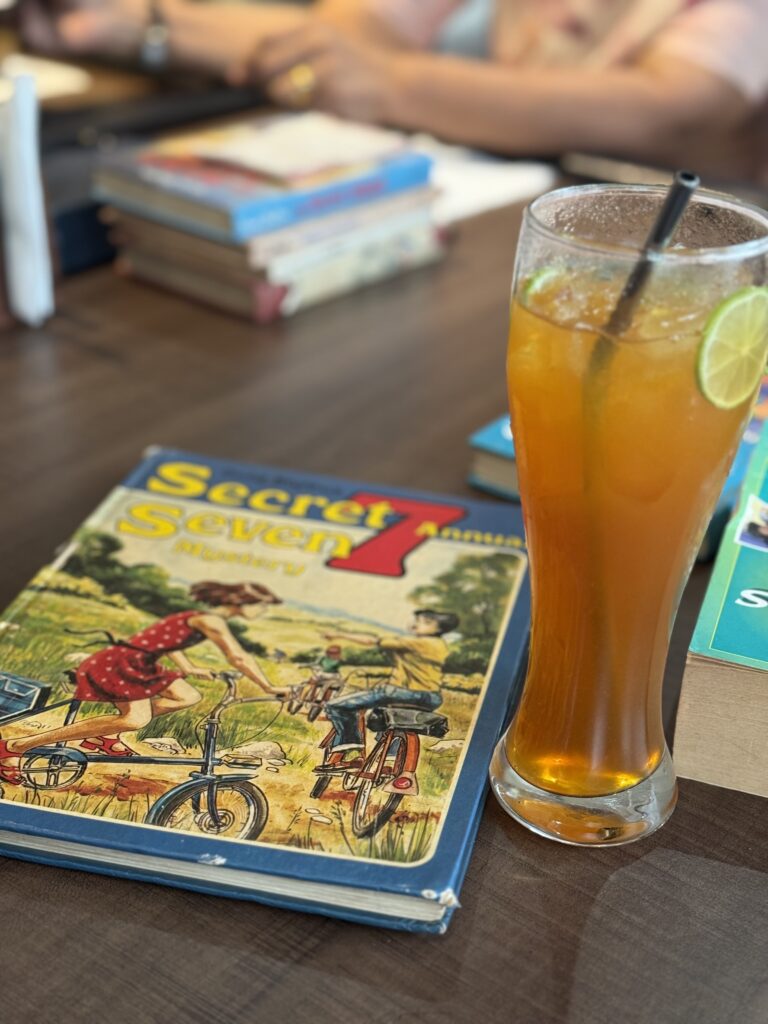

It has been ages since I last read an Enid Blyton, probably not since my school days. So when the theme for the upcoming Book Club meetup was announced as Enid Blyton, it felt like perfect timing. By pure luck I stumbled upon a Secret Seven Annual and picked it up without a second thought. A 1978 edition.

And with it came the bibliosmia of an old book. I am not even sure if it is a real word, but I will take it.

This Secret Seven Annual is a lovely little edition made for Secret Seven fans. Part story, part illustrations. Some pages have colourful pictures, others are in black and white, along with a crossword puzzle and even recipes from the Secret Seven world. Didn’t we all want to try that ginger beer, buns and scones? The Annual almost feels like a bridge between a magazine, a comic, and a children’s mystery novel.

The story itself is very simple. A missing girl, a bit of mystery, a money heist, and of course the Secret Seven trying to solve it. Nothing very complicated. The morals are simple and clear, nothing like the complicated dilemmas faced by superheroes in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Enid Blyton kept things uncomplicated, and I loved it.

But while reading it, I kept wondering something.

How did Enid Blyton manage to keep us so hooked with stories that were this simple?

The plots were straightforward. The language was easy. The characters were clear. No CGI magic. Just plain text. Yet when we read these books as kids, they felt like real adventures.

Enid Blyton gave us the story, but the rest of the work was ours. We had to imagine the houses, the gardens, the secret meetings, the hiding places, the countryside with its quiet villages. The book did not show us everything. Our minds filled in the gaps.

Today storytelling has evolved quite a bit. Kids encounter stories through many different mediums. Films, games, animated series, social media. The narratives are often more layered and the worlds are already fully built and visualised. Children’s stories now come with complex plots and even more complicated narratives.

The nature of storytelling has changed. Children now experience stories through games, world building, and cinematic universes. There are many different mediums to choose from. If a child does not enjoy reading, they can watch the Harry Potter film. If that feels slow or boring, they can step into the story through a role playing game, play as Harry or Hermione, explore Hogwarts, cast spells, fight dark wizards, and become part of the world itself.

But when we were reading Enid Blyton, the adventure happened mostly in our heads.

Reading this Secret Seven Annual reminded me that sometimes a story does not need to be complex to be memorable. Sometimes a small mystery and a few curious characters are enough.

So maybe the real magic of those books was not just the mystery or the adventure. It was the space they gave our imagination to play. We followed every clue, every discovery, completely absorbed. We wanted to be Peter or Janet or Fatty from the Five Find-Outers. We wanted to go out seeking mysteries. We formed secret clubs with rules, passwords, badges, and a secret meeting place, always on the lookout for suspicious strangers and strange events.

I think part of the reason is how storytelling worked back then.

Stories did not just stay inside the book. They spilled out into our lives.

Boredom played a big role in that. When there was nothing else to do, the mind wandered. And when the mind wandered, it started creating things. Stories became games. Games became little adventures, trespassing into places where we should not have been. Books quietly shaped the way we saw the world.

Today that boredom has been replaced by something else. Our attention is constantly occupied. There is always another video, another notification, another scroll waiting. The mind rarely gets that empty space anymore.

And maybe that empty space was important.

Because imagination needs silence. It needs time. It needs the freedom to wander a little.

So when we talk about books and reading, especially for children, maybe what we are really talking about is protecting that space. A space where a story moves from the page into the mind, and from the mind into life.

Leave a Reply