- Coming Out as Dalit by Yashica Dutt

- Anti–God’s Own Country – A Short History of Brahminical Colonisation of Kerala, A. V. Sakthidharan

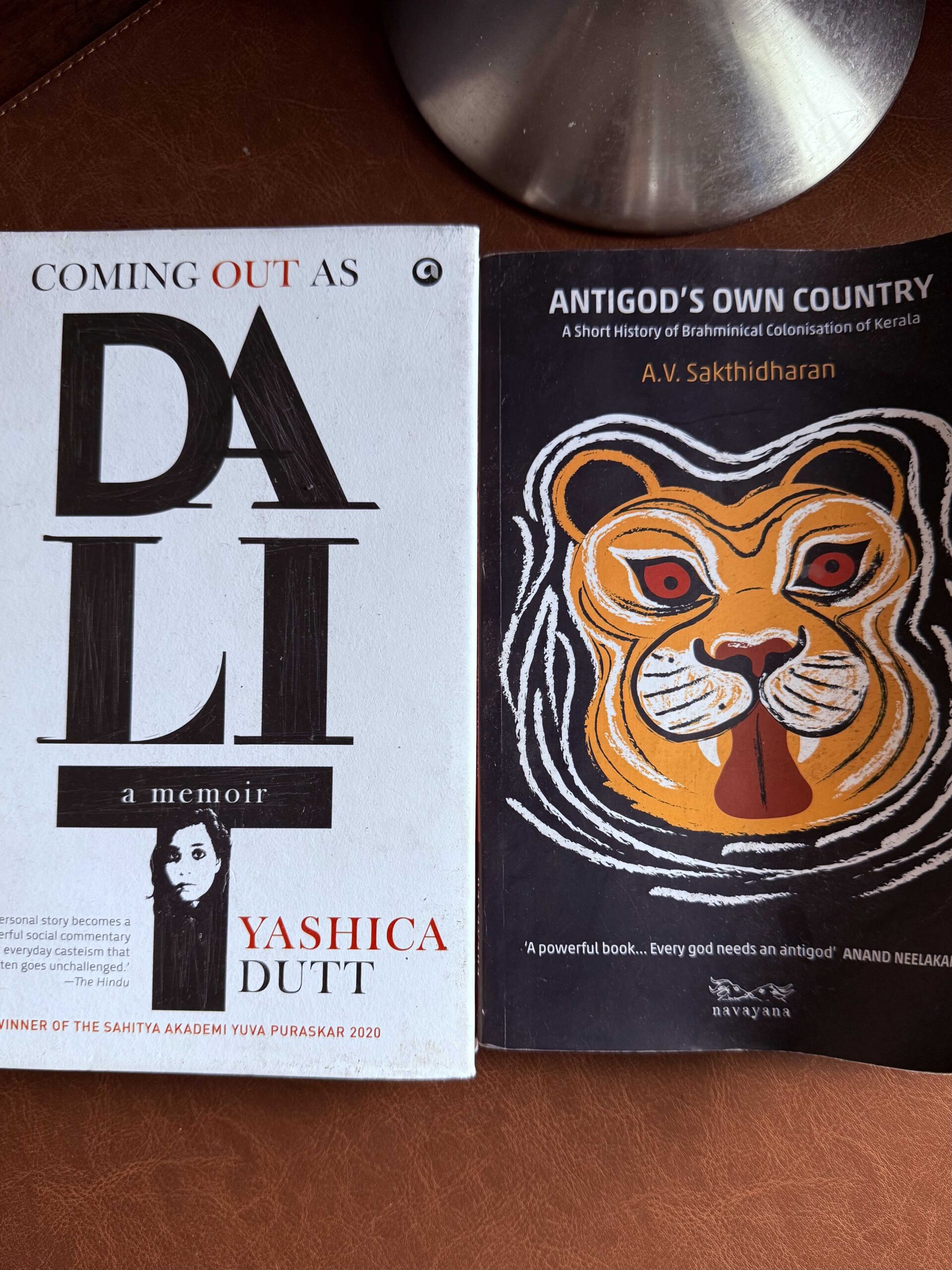

Two books I’d like to recommend are Coming Out as Dalit by Yashica Dutt and Anti–God’s Own Country – A Short History of Brahminical Colonisation of Kerala, A. V. Sakthidharan

Coming Out as Dalit by Yashica Dutt is a memoir in which the author narrates the burden and struggles of hiding her dalit identity and her tumultuous journey of coming out.

Dutt describes how Dalits are still seen as impure, dirty, or unworthy. Sometimes with and without overt slurs, there is a quiet, persistent dehumanisation—in schools, workplaces, and social spaces. Dalits are locked out of access to quality education, elite social circles, and career advancement unless they conceal their identity.

Yashica had to hide her caste to attend elite schools, knowing that a Dalit surname could shut doors. Though not personally subjected to physical violence, Dutt references cases like Rohith Vemula’s institutional harassment and suicide, Dalit students being ostracized or failed, and the rising number of atrocities in rural India. Even in metropolitan cities, caste operates subtly—in housing discrimination, hiring biases, marriage markets, and friendships. The urban elite deny its presence, which makes it harder to name or fight.

It would be easy to think that in this era of AI, ChatGPT, and rapid technological progress, a Dalit identity wouldn’t raise eyebrows anymore. Technologies have progressed, but society hasn’t kept pace. Caste may no longer be written on paper, but it still marks bodies, boundaries, and opportunities and even coded into biases within LLMs.

In Anti–God’s Own Country: A Short History of Brahminical Colonisation of Kerala, A. V. Sakthidharan presents a compelling counter-narrative to the widely accepted myths propagated by Brahminical historiography, dominant caste traditions, and state-sponsored cultural narratives.

He reimagines Kerala’s past not as the harmonious “God’s Own Country,” but as a land systematically colonised by Aryan-Brahminical forces. Sakthidharan depicts Maveli as a powerful and egalitarian ruler of Kerala’s indigenous people—one who was deceived and displaced by Vamana, a Brahminical avatar. This foundational myth, he argues, symbolizes the larger historical arc of caste imposition and cultural erasure.

The book explores how subaltern mythologies—those of tribal, Dravidian, Dalit, and Adivasi communities—were rewritten, demonised, or co-opted. Indigenous deities such as Murugan, Mutthappan, Pottan Theyyam, Ayyappan, and numerous mother goddesses were absorbed into the Brahminical fold, their rituals sanitised and stripped of their radical, egalitarian meanings. What were once vibrant expressions of resistance and community identity were transformed into sanitized, upper-caste-compatible religious practices.

Sakthidharan argues that Brahminical domination was not limited to the realm of religion—it extended into the economic and psychological fabric of society. The Aryan settlers claimed land, took control of temples and institutions, and instituted caste-based hierarchies that entrenched inequality materially and mentally. The colonisation of Kerala, he shows, was not just physical—it was spiritual, intellectual, and cultural.

Both Yashica Dutt and A. V. Sakthidharan offer narratives many of us would rather not hear—truths we prefer to push to the margins, buried under the comfort of ignorance. These aren’t distant horrors; they are lived realities for those we choose to ignore.

Leave a Reply